Recap of The Mobi 100 Jackpot ⛰️🏃

Introduction

In this post, I’ll be sharing my personal journey from the 2025 Mobi Jackpot challenge, part of the inspiring +442 Charity Run in Biel/Bienne. What started as a fun idea quickly turned into a real goal—something that got me moving every day, kept me focused, and made each climb feel like part of something bigger.

The +442 Charity Run

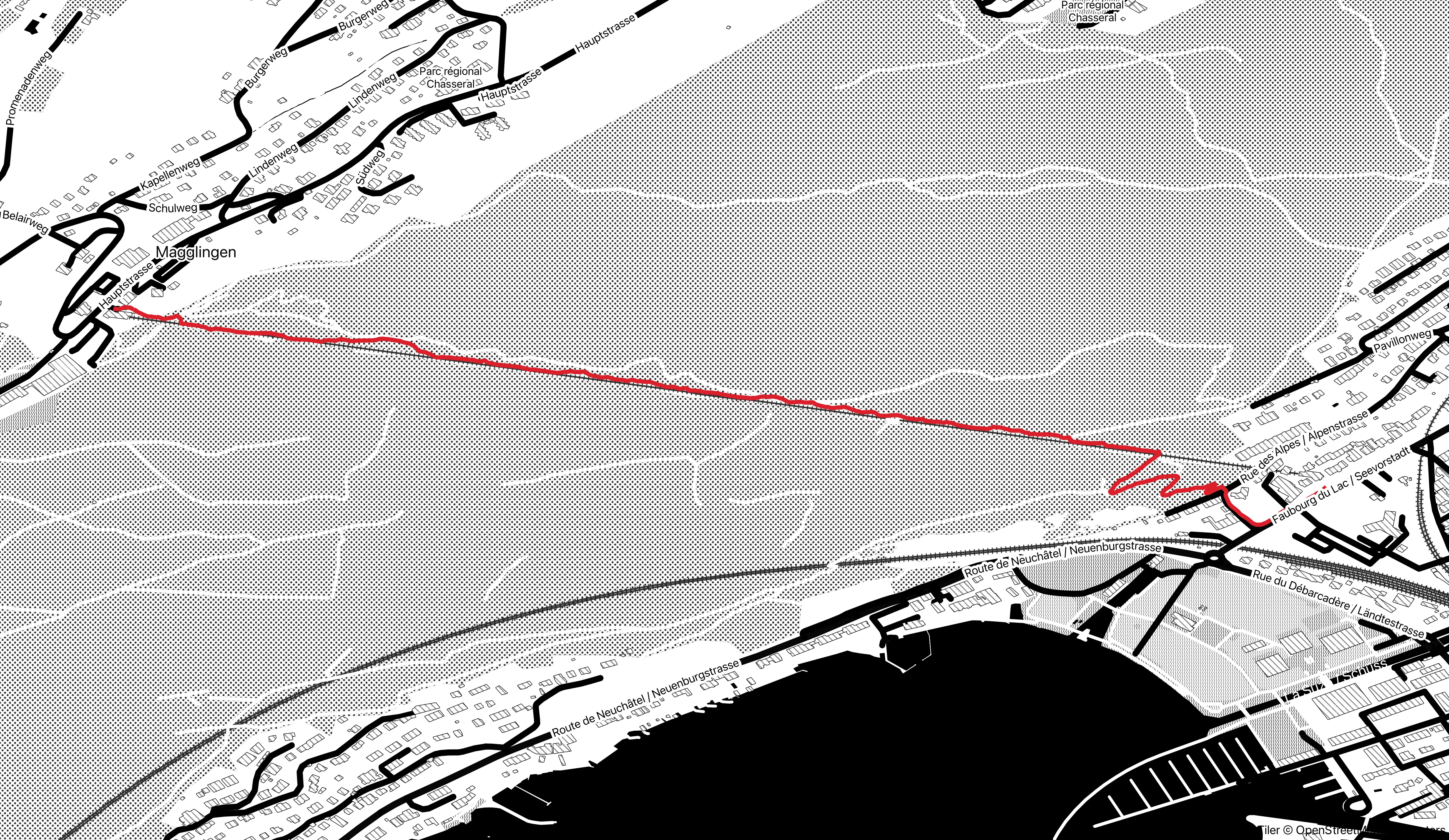

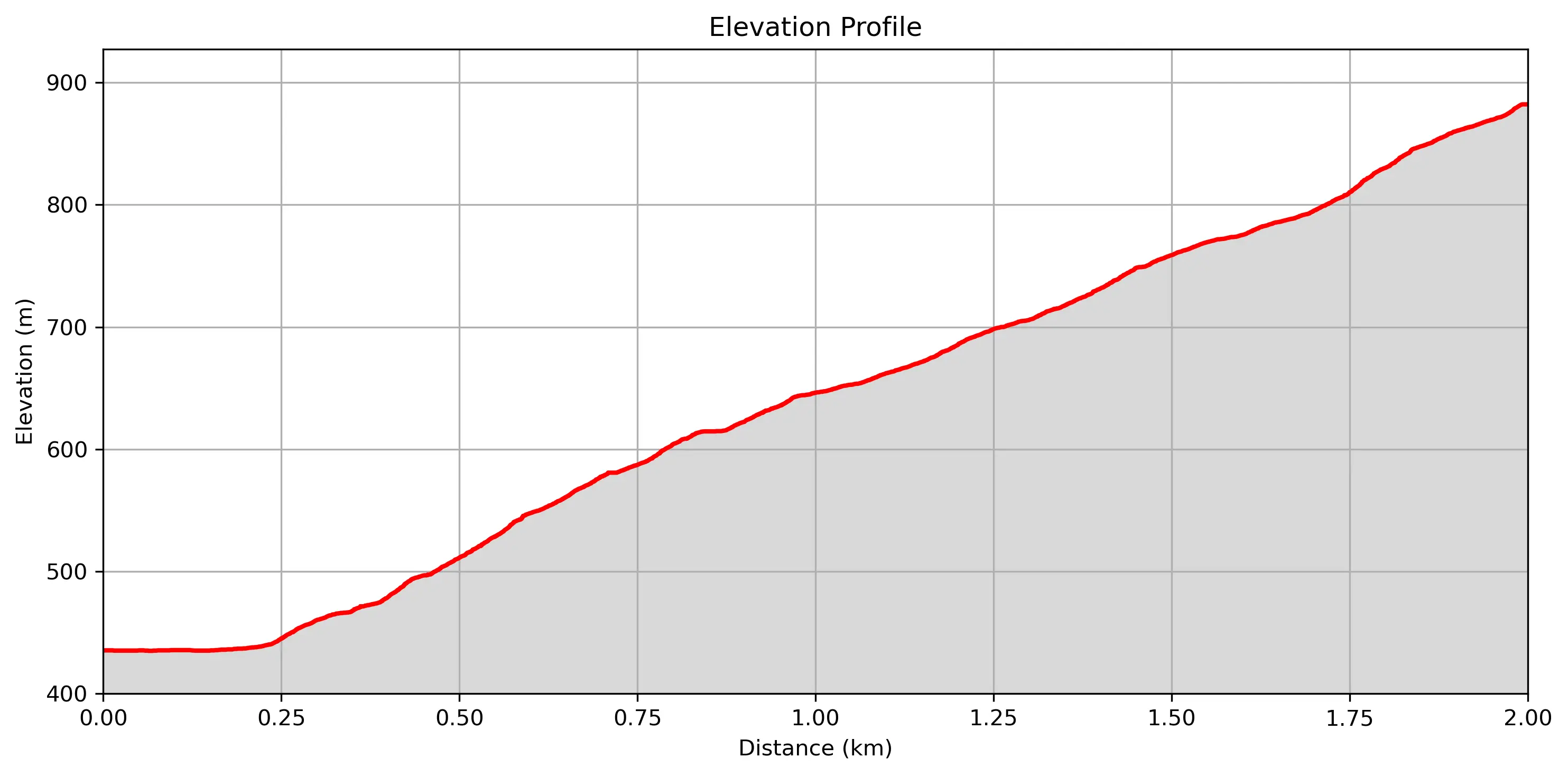

I first discovered the +442 Charity Run through a Strava group and wasn’t quite sure what to expect. It’s not your typical race—there are no medals, no timing chips, and no crowded starting lines. Instead, it’s a month-long, community-based challenge that invites people of all ages and fitness levels to climb the 442 meters from Biel to Magglingen—any way they like, and as often as they like—from May 7 to June 4, 2025.

Participants could run, hike, or walk the route—solo, in groups, with family, or even with pets. Each ascent was tracked via QR codes placed at the bottom and top of the Magglingen Funicular. Every climb triggered donations from sponsors, either per meter, per ascent, or as a flat amount. All proceeds supported the Förderverein für Kinder mit seltenen Krankheiten (KMSK), helping families of children with rare diseases. Additionally, 10% of the funds were directed to local cultural and social projects in the Biel area.

It’s a challenge rooted not just in fitness, but in purpose—turning every step uphill into something meaningful.

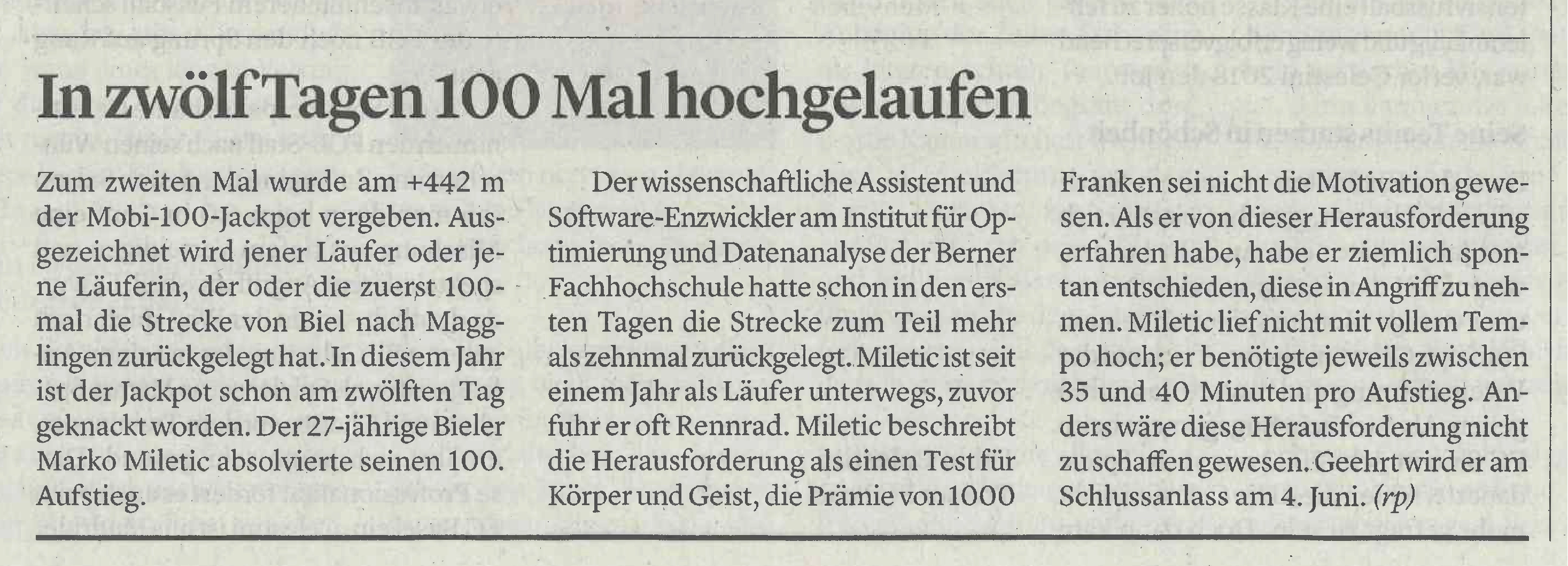

The Mobi 100 Jackpot

As I read more about the event, one particular element grabbed my attention: the Mobi 100 Jackpot.

The challenge? Climb the Biel–Magglingen route 100 times during the event. The reward? CHF 1,000 from the Mobiliar General Agency in Biel, awarded to the first person to complete this feat. The moment I read about it, I was hooked. 🎣

There was something thrilling about the idea—not primarily the prize money, but the test of endurance, the daily discipline, and the opportunity to be part of something that directly impacts the lives of children in need. The jackpot added a spark of competition to an already meaningful challenge, and I knew right then: I wanted to go for it.

The plan was straightforward: I had around eight days of overtime saved up at work. With two weekends added, that gave me 12 days total to complete the 100 ascents. Naturally, I aimed to finish in exactly 10 days—there’s something satisfying about round numbers. But in the end, it took all 12. One half-day was lost to bad weather, and another half-day to a spontaneous decision to take part in the Gassenlauf 🏃.

Given my plans to take part in other long-distance races soon, I made an early decision: no descents on foot. Walking or running back down 44,200 meters would be asking for a total breakdown of tendons and cartilage. The Magglingen funicular exists for a reason—and I intended to use it.

Another goal I set for myself was to complete the challenge fully self-supported. That meant no outside help: I would carry all the essentials—food, gear, supplies—on my own. I’d cook every meal, prep every snack, and be solely responsible for logistics. Spending 9 to 11 hours away from home most days demanded tight organization. I wanted my actions to have consequences. No shortcuts, no outsourcing.

Fun Facts

After completing 100 ascents, I took a step back and looked at the data. What I found was a weirdly personal mix of effort, routine, and numbers that now feel oddly intimate.

-

In total, I lost over 54 liters of sweat — enough to fill a carry-on suitcase, soak through more than 270 T-shirts, or keep a cactus alive for over a decade. I didn’t expect to be doing hydration math, but here we are.

-

I burned over 34,000 kilocalories, which is roughly the equivalent of 135 avocados… or 60 Big Macs. Over the twelve days, I dropped around 2–3 kilograms of body weight.

-

The total elevation gain was just shy of 44,700 meters — nearly five trips up Mount Everest. It’s the kind of stat that makes you wonder how your knees are still holding up.

-

My heart rate stayed mostly in the 140–150 bpm range, though there were a few spikes up to 230 bpm. Probably a sensor glitch. Hopefully.

-

My average pace per day was about 18 minutes per kilometer, with the slowest days clocking in at 22 minutes and the fastest somewhere around 14.

-

According to Garmin, my Body Battery hated every minute of it. Most sessions ended deep in the red — not shocking, given that “recovery” mostly involved sitting on the floor and staring into the void.

-

I averaged 70–80 steps per minute, with a stride length of about 0.75 meters. Power output hovered in the 250–270 watt range, with occasional spikes over 900 — probably the result of a steep incline… or mild panic.

Media Footprint

The Bieler Tagblatt featured the Pipeline Power challenge and the Mobi Jackpot in a recent article. You can read a short excerpt regarding the Mobi Jackpot below.

© Bieler Tagblatt. All rights reserved.

Event Diary

What follows is my diary from the twelve days of chasing climbs, chasing meaning, and chasing the 100.

Pre-event

-

In the days leading up to the event, I was still deep in work mode—working on a paper resubmission on synthetic data in pharmacogenetics, which was nearing publication. It’s finally published here 🎉. By 6 p.m. the evening before the race, the paper was submitted, and with that, the weight of professional responsibilities lifted. I could finally shift my focus entirely to the challenge ahead.

Two days before the event, I slipped and twisted my foot while walking down wet stairs—a brief scare that made me think my participation might be over before it even began. Luckily, it turned out to be nothing serious. It still hurt to walk, but not enough to stop me. It served as a reminder of how fragile these opportunities can be—how a single moment of inattention can derail something you’ve looked forward to for weeks or even months.

Wednesday (Day 1)

-

The official start of the +442.run event was May 7th at 4 p.m.—thankfully in the afternoon, which gave me time to shop for groceries, prep meals and snacks, and take care of some housework. There’s nothing worse mid-challenge than realizing the dishwasher is full and you’re out of clean plates.

A coworker I occasionally go biking with offered to join me for the first ascent. Since he didn’t carry me, the self-supported rules remained unbroken.

The goal for Day 1 was five ascents. Starting a multi-day event like this can be mentally tough—especially when you feel like an outsider. It was my first time doing anything like this, and I’m still relatively new to the city. Having company for the first lap helped ease me into it. Thankfully, the +442.run crowd turned out to be just the kind of people you hope for in endurance events: kind, welcoming, and full of good energy.

To track ascents, the event uses QR codes—one at the base station of the Magglingen funicular, and another at the top. You scan in at the bottom, scan out at the top, and the system logs a completed ascent. Pretty soon, this ritual—scanning both codes and starting/stopping my watch—became a familiar rhythm in the long journey toward 100 climbs.

On the final descent of the day, I sat next to a woman who, it turned out, was the wife of one of the event organizers. Small world. I told her I’d just finished my five ascents and shared my plan for the full 100. She looked surprised, but gave me an encouraging nod—like she approved of the madness.

A few minutes later, just before the funicular departed, another group of four joined our section. The woman struck up a conversation with them—they clearly knew each other—and they started chatting about the “Wake-Up Run” scheduled for Saturday at 5:30 a.m. They asked if I was joining. I said I had other plans and needed to recover properly if I wanted to survive the days ahead. One by one, they all came up with reasons why they probably wouldn’t make it either.

Then, with a grin, the woman turned to them and said, “He’s already done five ascents today. He’s going for the Jackpot.” One of them looked at me, eyes wide: “What? Five already? And you’re aiming for 100?” I explained my plan, and she turned back to the group and said, “Okay, we have to be quiet now. This strategy needs to stay a secret—otherwise, the competition will adjust, and the Jackpot might be in danger!”

Soon after, we reached the valley station, wished each other luck—whether for a hundred ascents or a brutally early wake-up—and parted ways. Just like that, Day 1 was complete. Faster than expected, the journey had begun.

- Distance

9.52 kmTime

2:57:21 hAvg. Pace

18:37 min/kmElevation Gain

2,225 mCalories

2,528 kcal⛰️ Total Ascents After Today: 5 -

Thursday (Day 2)

-

With legs still relatively fresh, I stepped out of the house and began Day 2—my first of several days planned with 10 ascents each. Mornings were always chilly, but once the sun had been out for a few hours, the temperature began to rise quickly, making things much warmer and more comfortable.

The first section of the trail—where you pass a few stairs before entering the forest path that leads toward the Pavillon—had a recurring challenge: ermine moth caterpillars. Or more precisely, loads of them.

These little guys weave communal larval webs in the bushes beside the trail and in the trees overhead. But the real hazard wasn’t just the webs—it was that they rappelled down from the trees like tiny, uninvited paratroopers. If you weren’t paying close attention to the trail, chances were good you’d collect a few passengers on your clothes. I always recommend breathing through your nose for efficient airflow during exercise—but if you happened to forget your protein bar at home, just open your mouth and you might get a bonus hit of juicy trail protein. To each their own. 😉

After my third ascent of the day, I scanned the QR code at the top station and headed inside to catch the funicular back down. That’s when things briefly took a turn. A staff member stopped me from boarding and pointed out a sign I hadn’t noticed: “Planned Power Outage between 10:00–12:00.”

My mind started spinning—Seriously? Already infrastructure issues on Day 2? I started weighing my options:

Walk down? That would mean extra strain on the joints and still falling behind.

Wait it out? Risk wasting precious time and missing my 10-ascent goal.

Thankfully, the woman explained further: the power had just come back on, and the system was in the process of rebooting. The next funicular would probably depart within minutes—though there was still some uncertainty. It made for a tense few moments, but in the end, everything went smoothly. The funicular resumed normal operations without delay. Disaster averted. The last

Later that day, I also cooked meals for the next couple of days and managed to squeeze in a quick 15-minute wash cycle to freshen up my clothes. All part of the self-supported routine—preparing for each day like it’s a mini-expedition.

- Distance

19.31 kmTime

6:50:59 hAvg. Pace

21:16 min/kmElevation Gain

4,448 mCalories

4,315 kcal⛰️ Total Ascents After Today: 15 -

Friday (Day 3)

-

When the clock rang in the morning I got up right away even though I was still very sleepy and in need of recovery. It’s funny when you have set yourself a clear goal for the upcoming days it’s not a problem to wake up in the morning. However on other days where you’re just seemingly living everyday day to day life sometimes it’s much harder to wake up in the morning I have noticed. Maybe the same goes for you?

To further boost morale I spontaneously decided to have a coffee before I go out for the next 10 ascents. As described earlier I wanted my actions to have consequences and this coffee had the consequence that ehmm. you know what usually happens after you drink coffee… let’s just say that it delayed my start of the day by a couple of minutes.

If I recall correctly on the second ascent of the day at the top station there was an older woman that struck up conversation with me. She seemed annoyed and I said whats up? She spend sometime on her phone infront of the sign where the QR-code is placed for the check out. She explained to me that she always has to login again on the +442 website. And how annoying it is that they made it like that. Further she complained that it is the same thing for her newspaper subscription. Coming from an informatics background and being tech savy I immediately had a culprit in mind. So for the next few minutes I helped this woman open a new tab which wasn’t in incognito mode and where therefore login information in form of cookies is saved in between sessions so she does not need to login each time. It was a nice being able to help somebody with such easy measures. She said thank you and how awesome it is now that she won’t miss future funicular descents because of arriving minutes before and not making it because she has to login again time after time. Afterall for such an event and life in general time is of the essence. Kind of stupid of me to help my competitors but not at all be kind help where you can is the motto i strive for!

There are parts of the trail where when the funicular passes you can see the people inside of the funicular and they can see you back. Guess who waved hysterically from the funicular on her way down after seeing me holding a coffee in her hand that she had enough time to allocate for getting a coffe instead of spending time logging in. The world can be simple be nice regardless of circumstances and sometimes you get nice gestures in return that motivate you and give you energy to continue on the day. Making the ascents just a little more bearable.

On the last ascent before lunch I was suprised by two coworkers with homemade cake by one of them! They went up with their road bikes to see how fast one is compared to walking up or taking the mountain bike through the forrest. This is the only time where the self support rule was okay to break and the only time it happend. I just couldn’t not accept such a nice gesture.

At the end of the day three after the last ascent I met the guy who won last year and had a little chat. He asked me if I had any previous experience with ultras and guessed by my looks that I probably have a background in playing football. But no I didn’t have any prior experience on Trail-running or even Ultra-running. He gave me some encouraging words and we both went on our merry ways.

- Distance

19.19 kmTime

6:06:49 hAvg. Pace

19:07 min/kmElevation Gain

4,454 mCalories

4,005 kcal⛰️ Total Ascents After Today: 25 -

Saturday (Day 4)

-

In the morning, I couldn’t help but admire how quickly some people managed to power up—and back down—the course. One local ultra runner impressively completed two runs without using the funicular in the time it took me to finish my first and second attempts of the day. Still, something far more meaningful happened that day: it was Family Day at the +442 course.

Since the event raises money for children with rare diseases and their families, the organizers wanted to further highlight that spirit. This year, they introduced a special Family Day, designed specifically for families and kids.

No registration was required, and the motto was simple: there are no winners—taking part is everything. The day was organized with the help of Pfadi Orion and Naturschule See Land, two fantastic organizations that know how to bring joy to outdoor learning and play.

From 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., families could explore a variety of fun activities tailored even for the youngest running enthusiasts. These included tin can tossing, quizzes about the event and the funicular, and more. Midway up the course, a slackline was stretched between two trees—inviting children to test their balance after hiking or running a good chunk of elevation. Not as easy as it sounds, especially on tired legs!

Near the Hohenfluh middle station, children had the chance to make Schlangenbrot over a fire and practice knot tying. Learning to tie knots isn’t just fun—it helps build fine motor skills, spatial awareness, memory, and problem-solving abilities. A truly thoughtful addition by the organizers.

Many of the volunteers not only helped organize the Family Day but also took part with their own children. Attendance was modest, likely due to it being the first time the Family Day was held—or perhaps because the Grand Prix Bern took place on the same day. The weather certainly wasn’t to blame: it was ideal—not too hot, with plenty of sunshine.

Here’s hoping word spreads and more families join in next year. It’s a wonderful initiative, and I’d love to see it grow.

- Distance

19.30 kmTime

6:30:50 hAvg. Pace

20:14 min/kmElevation Gain

4,443 mCalories

3,849 kcal⛰️ Total Ascents After Today: 35 -

Sunday (Day 5)

-

There were noticeably more people on the trail today than during the week—which makes sense. Most people work Monday through Friday and save the weekend for getting outside and doing things like this.

The weekend rhythm, with its patterns of rest and activity, actually made me think of the phrase “Nuns don’t work on Sunday,” from a memorable scene in Magnum, P.I. In that episode, Magnum is tracking an international assassin named David Bannister, known for his disguises. Bannister plans to strike during a Sunday church service, disguised as a nun. Magnum searches through the congregation but struggles to spot the fake—until it hits him: real nuns typically don’t work on Sundays. That small but telling detail helps him identify the assassin.

Long story short: that scene came to mind because I decided not to push for 10 ascents today. My body needed some recovery.

Instead, I had a different kind of experience. I met a woman who had also caught the +442 fever. If she keeps climbing as regularly as she is now, she’ll probably end up with the second-highest number of ascents this year. We struck up a conversation in English, which often becomes the go-to language in bilingual cities like Biel/Bienne. It was refreshing to share words and steps with someone along the way.

It made me think of a line from Ben Howard’s song Follies Fixtures: “Walk with me until I find some meaning.” That lyric stuck with me. Maybe meaning isn’t something we suddenly discover—maybe it unfolds gradually, through companionship. Through shared silences, casual chats, or simply walking side by side.

There’s something grounding about syncing your pace with someone else’s, especially when you’re both climbing the same hill—literally or figuratively. It doesn’t make the mountain smaller, but it makes the climb feel lighter. And maybe that’s part of the meaning too: not just the destination, but the experience of getting there with someone who understands the journey, even if it’s just for a little while.

Later that day, I also did some meal prep for the coming days: Hörnli mit Gehacktem, rice pudding, and banana bread.

- Distance

9.64 kmTime

3:17:04 hAvg. Pace

20:25 min/kmElevation Gain

2,218 mCalories

1,805 kcal⛰️ Total Ascents After Today: 40 -

Monday (Day 6)

-

It rained during the night, and by morning the trails were slick and treacherous. In that moment, I truly appreciated how fortunate I’d been with the weather so far—nearly all days were of sunshine and ideal hiking conditions.

But this day felt different. The entire trail looked and felt transformed. The city of Biel was wrapped in a dense fog. At the start of the trail, visibility was just a few meters ahead. As I ascended, the fog slowly lifted, sometimes even giving way to sunshine at the summit. The mist seemed to travel with the trail—sometimes cloaking the middle stretch, sometimes blanketing the top. It became a kind of rhythm: from darkness to light, and occasionally, back into the grey.

By lunchtime, the trail had become so slippery that I swapped out my lightweight trail runners for proper hiking boots and geared up with a heavier rain jacket. The steady drizzle eventually turned into a heavy downpour. After completing the eighth ascent, I returned to the bottom station, took a break for some water and snacks (yes, staying hydrated is still important even in the rain!), and reflected. Wearing a rain jacket keeps you dry from the outside, but you’ll still get soaked from the inside thanks to poor breathability. After about 10–15 minutes, I decided to call it a day. Not a defeat—more of a strategic retreat.

…though even saying that sounds a little pretentious.

I couldn’t help but laugh imagining how someone on LinkedIn would spin this into an inspirational life lesson. You know the type—someone posting under #grit or #resilience with a story so saccharine and self-congratulatory you’d need sunglasses to read it.

For no good reason other than amusement, here’s my go at channeling the most insufferable LinkedIn personality imaginable:

Marko MileticFounder • Chief Resilience Officer • Mobi Jackpot Finisher6h • 🌍🌧️ The rain was relentless. The trail? Unforgiving. Most would’ve turned back.

Marko MileticFounder • Chief Resilience Officer • Mobi Jackpot Finisher6h • 🌍🌧️ The rain was relentless. The trail? Unforgiving. Most would’ve turned back.

But I’ve never been “most.”

On the eighth ascent, soaked to the bone, I made a choice: not to quit — but to pivot. Not out of defeat, but out of discipline.

Leadership isn’t just about charging forward. It’s about reading the terrain, assessing risk, and knowing when to pause with purpose.

I didn’t reach the summit that day. But I leveled up in a more important way: I made a call from clarity, not ego.

📌 You don’t always conquer the mountain. Sometimes, you ARE the mountain.#Unshakeable #ResilientLeadership #BuiltDifferent #FounderFuel #EliteResilience💼 248 • 💬 37 • 🔁 12 •••Anyway… that was day six. I didn’t finish the entire route that day, but I did gain a new appreciation—for the plants that love the rain, for the changing trail, and for how much greener everything seemed, even with the clouds above.

- Distance

15.52 kmTime

5:16:23 hAvg. Pace

20:23 min/kmElevation Gain

3,575 mCalories

2,835 kcal⛰️ Total Ascents After Today: 48 -

Tuesday (Day 7)

-

Like in life, sometimes in sports you fall behind—and that’s exactly what happened to me yesterday. Bad weather threw off my plan, so on day seven, I had to catch up. To stay on track for my goal of 60 ascents, I needed to get 12 done in one day. That’s the most I’ve had to do so far in this Mobi Jackpot.

On that first ascent, I stood at the base of the trail looking up at the steps, just thinking, “Can I actually do this?” The day already felt long, and I hadn’t even started.

That’s when a line from Rudyard Kipling’s poem “If—” came to mind: “If you can fill the unforgiving minute with sixty seconds’ worth of distance run…” It’s a line I’ve heard before, but in that moment it landed differently. Kipling wrote “If—” in 1910, placing it at the beginning of a story called “Brother Square-Toes”—a tale about a quiet, principled Quaker named Pharaoh Lee who navigates the political chaos of the 18th century with calm and steady resolve. The poem, though not part of the plot, sets the tone: it’s about keeping your head, doing your duty, staying grounded, and not giving up—even when it’s hard, unfair, or exhausting.

That spirit really hit home for me. I was behind. I was tired. But none of that mattered to the mountain. None of that changed the goal.

So I didn’t overthink it. I just started. Left foot, right foot. One step at a time.

The trail doesn’t care how tired you are. The clock doesn’t pause because your day got rained out. You either get back to it, or you don’t. And I was so locked in—so focused on getting through it—that I didn’t take a single photo or jot down a note all day. I was just climbing.

That same day, a primary school class happened to be on the trail too. A coworker of mine has a flatmate who’s a teacher, and she had told her students that someone was going for the Mobi Jackpot—climbing up to 10 times a day. Apparently, they were using that story to motivate the kids. Apparently I’m becoming folklore.

I ended up passing the last group of the class twice. The second time, one of the students looked at me and said, “Haven’t I seen you already today?” I just laughed and said, “Yeah, this is my seventh time going up.”

The teacher gave me a smirk and said, “Not bad. But there’s someone doing 10 a day.”

I smiled and replied, “Yeah… that’s me.” She started laughing. Turned out her coworker—the flatmate—was the one who told her. We ended up having a fun little chat on the way down in the funicular.

Twelve ascents and over seven hours of moving time later, I was back on track.

- Distance

23.13 kmTime

7:18:25 hAvg. Pace

18:57 min/kmElevation Gain

5,347 mCalories

4,073 kcal⛰️ Total Ascents After Today: 60

Wednesday (Day 8)

-

The next morning, I woke up and saw a Strava notification: someone from Canada had started following me. Naturally, I was curious. I checked out his profile and saw that he was doing very similar activities—hiking and trail running up steep mountains, then taking a cable car back down.

I started wondering if there was a similar event going on in Canada. After a bit of digging, I came across the Grouse Grind® in Vancouver, British Columbia. It’s a 2.5-kilometre trail straight up the face of Grouse Mountain, often called “Mother Nature’s Stairmaster.” The climb gains 800 metres (2,624 feet) in elevation and includes a brutal 2,830 steps. Hiking back down isn’t allowed—most people take the gondola down, just like we do here. (Although here, you’re free to hike down too if you want.)

The Grouse Grind is a big deal—over 100,000 people tackle it every year, and some locals even do multiple ascents in a single day. They track their times with something called a Grind Timer card. It’s wild to see how similar challenges exist around the world, and how they create a kind of quiet connection between people who’ve never met but are doing the same kind of crazy stuff.

Turns out, this Canadian connection happened through one of Strava’s global events: the May Elevation 2025 Challenge, which had a goal of reaching 2,000 meters of elevation gain during the month of May. After finishing the Mobi Jackpot and wrapping up the month, I somehow ended up in 8th place worldwide with a total of 46,242 meters of elevation gain—out of 373,597 participants. That’s a 2,312% completion rate.

The guy from Canada? He logged a ridiculous 100,853 meters—over 50 times the challenge goal—with a completion rate of 5,043%. Absolute beast.

Honestly, this probably won’t happen again anytime soon. A coworker joked that I should be careful—I might be drifting into dangerous waters: the ultra community. But honestly? Forget that. These people are awesome.

Knowing that someone across the world is going through something similar really helped me ease through the day.

There’s something strangely grounding about that realization. Even though I’ve never met this person, and we live on opposite sides of the planet, we’re both waking up early, lacing up our shoes, and pushing ourselves up steep, relentless trails—day after day. He even more than me! It’s not just about the physical effort. It’s the rhythm, the repetition, the mental game. And somehow, knowing that someone else is voluntarily choosing that same struggle made mine feel a little lighter.

It reminded me that the challenges we take on—especially the self-imposed ones—don’t exist in isolation. There’s a whole community of people out there quietly doing the hard things, too. No finish lines, no crowds, no medals. Just personal goals, early mornings, tired legs, and quiet satisfaction.

On that eighth day, when my body felt worn and my mind started to drift, thinking about this random Canadian stranger helped center me. It wasn’t about comparison or competition—it was about connection. A reminder that while every trail is different, the grit it takes to keep climbing is a shared language. And that’s pretty cool.

- Distance

19.31 kmTime

5:53:46 hAvg. Pace

18:19 min/kmElevation Gain

4,409 mCalories

3,263 kcal⛰️ Total Ascents After Today: 70

Thursday (Day 9)

-

On the first ascent of the day, I unexpectedly encountered a roe deer. Apparently, I was moving so silently up the hill that I startled it at a range of just five meters. In a flash, it dashed into the undergrowth, letting out a series of sharp, barking sounds—something that completely caught me off guard. Although I’ve photographed roe deer in the past, I had never heard them make such noises. Curious, I later looked it up and discovered that this barking is a known alarm call, used by roe deer to warn others nearby of potential danger. Fortunately, I was quick enough to pull out my phone and capture a snippet of the sound, which can now be heard under the audio tab.

Later in the day, during my second or third ascent, I spotted another slow worm basking right on the trail. Its smooth, bronze-colored body stood out against the path, glinting faintly in the light. As with others I’ve seen, it was motionless at first, likely soaking up warmth before retreating to its more hidden, burrowed world. These shy, legless lizards are always a fascinating find—quiet, ancient-looking creatures that seem to embody the mystery of the undergrowth.

Shortly afterward, I came across yet another slow worm, this time just as another runner came down the trail. We both stopped to let each other pass, and I pointed at the ground and said, “Be careful not to step on it.” He paused and replied that it was the second one he had seen today as well. We exchanged a few words, and I learned that in French, the slow worm is called orvet.

In the afternoon, after several more ascents, I was sitting in the funicular waiting for it to begin its descent. When I glanced at my watch to check the time, I noticed a tick crawling along my wrist. It was actually the second tick I had seen during this event—the first had appeared on one of my socks earlier in the day. The life of this second tick was short-lived, however, as I promptly crushed it with the carbide tip of my Leki pole against the ground.

Encounters like these are a reminder of how much life exists quietly alongside the trail. From deer issuing alarm calls to legless lizards basking in brief moments of sunlight, and even the unwelcome appearance of ticks—these animals are all part of the same landscape we move through. It’s striking to consider how our presence, even as careful hikers or runners, can ripple through their world: startling a deer into flight, forcing a slow worm to retreat early from its basking, or simply shifting the natural rhythm of a quiet hillside. That said, one thing that stood out to me was how clean the trail remained throughout the event. Despite the number of participants, I didn’t see any litter or signs of carelessness. Runners were clearly respectful of the environment, leaving no garbage behind—a small but significant gesture that helps protect the delicate balance of these shared spaces.

In the end, these moments—unexpected and fleeting—are small reminders to move with awareness and respect. The trail doesn’t just belong to us. It winds through a living, breathing ecosystem, full of creatures whose lives are more delicate and intertwined with our own than we often realize.

- Distance

19.31 kmTime

6:23:32 hAvg. Pace

19:52 min/kmElevation Gain

4,423 mCalories

3,277 kcal⛰️ Total Ascents After Today: 80 -

-

Friday (Day 10)

-

On this day, I spontaneously ended up doing a few sub-30-minute laps with the same guy who, just the day before, had stopped to chat about the slow worms. It was a refreshing change of pace and a welcome motivator to push a little harder. Even though I was already 80 ascents deep into the challenge, I felt good and decided to have some fun with it.

I think this was also the day I finally decided to switch to a running vest I had lying around at home. And oh my god—one of those moments where you ask yourself, why didn’t I do this sooner? All my snacks and drinks fit perfectly, and since I always used poles, I never needed to stow them away. It instantly made things more comfortable and efficient.

The other runner had placed a backpack near the top station with food and drinks so he could resupply each ascent. That was something I hadn’t really considered. I had committed to carrying everything I needed on my back, thinking the extra weight would add a bit of difficulty. And while it did, it wasn’t too much—just enough to feel it, but not enough to slow me down significantly.

We ended up talking a lot during the descents in the funicular. Conversations ranged from other events to training, to running and sports in general. I got to learn something about a person I might never have otherwise approached. We shared insights, exchanged ideas—all without ever knowing each other’s names. How awesome is that? No ego, no pressure. Just two people connecting over a shared experience.

And then—something you just can’t make up—I was given an orange. Why is this significant? A few weeks before this event, I had written a blog post about the poem Orange by Wendy Cope. In that moment, the sentiment of the poem really hit home: finding joy and peace in the ordinary. I was genuinely grateful for that orange. It lifted my spirits and, with the help of a little natural sugar, gave me a surprising second wind for the rest of the day. And just like that I was at 90 ascents.

When I got home that evening, I noticed a tick had bitten me on the inside of my right biceps. If you get a tick, it’s important to remove it carefully and monitor the area for any redness, swelling, or movement of the rash, as these can be early signs of infection. A good pro tip: store the tick in a small container or bag. That way, if you get sick later, healthcare professionals can test it to help determine whether it carried any diseases.

- Distance

19.24 kmTime

6:09:00 hAvg. Pace

19:12 min/kmElevation Gain

4,435 mCalories

3,334 kcal⛰️ Total Ascents After Today: 90

Saturday (Day 11)

-

This morning, I got back at it again around 8:00 AM. Today was the “+442 Pipeline Challenge,” where a group of runners had gathered as early as 4:42 AM to complete as many ascents as possible within 442 minutes. That meant they had until 12:04 PM to clock in their last run. I didn’t join that early, as I had already promised a coworker to participate in another sports and fundraising event—the Gassenlauf—in the afternoon. Nevertheless, I joined the challenge for five ascents starting from 8:00 AM.

It was a nice start to the day, especially since I was already warmed up from yesterday’s faster ascents. There’s something special about ascending as a group—it gives you a steady rhythm and keeps you motivated. I joined the main pack and successfully kept up for all five climbs. The overall pace today was much faster than in previous sessions, largely because the group always ran the flatter parts of the trail: from the base station to the first stairs, around “Hohefluh,” and through other runnable sections farther up.

The organizers had set up a small aid station at the top, offering water, bouillon, bananas, sandwiches, and more. Participants could also leave their gear there, as someone was always watching over it. This setup definitely helped people move more efficiently—no need to carry extra weight, and quick access to food and drink made a big difference. Some of the fastest runners managed 11 laps, with a few even running back down instead of using the funicular. Very impressive. The first descent had to be done on foot by everyone since the funicular wasn’t running that early, but after that, most people used it for the return.

At exactly 12:04 PM, everyone made their way down for a small ceremony where the winners were announced. I was generously handed an alcohol-free beer and a sandwich, which I gladly accepted before heading home to prepare for the afternoon event: Gassenlauf.

At 1:30 PM, participants gathered to collect their race numbers. The course was a 250–280 meter loop around Biel’s old town. This small-scale charity event ran in three 30-minute heats, each an hour apart. The slogan of the event was: “Not everyone has it easy! We run in solidarity with people affected by poverty.”

I decided to support my coworker by pledging CHF 2.50 per lap he completed. The event had a friendly, welcoming atmosphere—lots of families and kids cheering on the runners. It was a stark contrast to the morning’s challenge, where you’re often running alone, with no crowds, no fanfare. And honestly, I think I enjoy that quieter type of effort more.

Still, it was a good experience. I met my coworker’s parents and a few others as well. One of his friends had brought her child, who managed to take surprisingly good photos of us while running. It’s always fascinating to see how comfortably even four-year-olds handle mobile devices—definitely digital natives!

After the Gassenlauf, I briefly considered heading back to the other trail, but that idea quickly faded once I developed some stomach pains. In hindsight, maybe going all-out at a 5:10 min/km pace on the Gassenlauf after five morning ascents (averaging 14:54 min/km) wasn’t the best idea—especially not after drinking a beer and scarfing down free sandwiches. The weather also started turning bad in the evening, so I didn’t feel too bad about calling it a day.

- Distance

9.54 kmTime

2:22:08 hAvg. Pace

14:54 min/kmElevation Gain

2,219 mCalories

1,662 kcal⛰️ Total Ascents After Today: 95 -

Sunday (Day 12)

-

After a demanding Saturday, the goal for Sunday was straightforward: complete just five more ascents to reach 100 and finish the Mobi Jackpot 100 challenge.

I did the first two ascents on my own. Then, fittingly, I was joined by the same coworker who had done the very first ascent with me on Day 1. He wanted to be there for the final three climbs as well—and that’s exactly how we wrapped it up, together.

He also took some photos during the day, so I won’t write too much more about it. We finished the effort with a well-earned coffee at Restaurant Bellavista in Magglingen to quietly celebrate the achievement.

And just like that, the event was over—for me, at least.

I didn’t manage to complete it in my original target of 10 days, but finishing in 12 is still good. We made our way back home to rest and recover—because the next day, we had plans to scout the Bieler Lauftage 100 km course by gravel bike, which is coming up soon.

- Distance

9.63 kmTime

2:47:29 hAvg. Pace

17:24 min/kmElevation Gain

2,228 mCalories

1,672 kcal⛰️ Total Ascents After Today: 100 -